Chronic kidney diseases are highly diverse, but among them, there is a type of chronic kidney disease that may start showing signs in childhood. However, early symptoms are often subtle, leading to neglect by parents or misdiagnosis by doctors, resulting in delayed treatment. Moreover, this disease is hereditary, posing a high risk of developing into kidney failure, ultimately requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation to sustain life. This often-overlooked chronic kidney disease is known as Alport Syndrome.

Overview of Alport Syndrome

Alport Syndrome is a genetic disorder characterized by hematuria (blood in urine), proteinuria (protein in urine), and progressive renal function decline. Some patients may also experience sensorineural hearing loss and eye abnormalities, leading to its alternative name, eye-ear-kidney syndrome.

According to the reports, the genetic frequency of Alport Syndrome in U.S. is estimated to be 1/10,000 to 1/5,000. The incidence and severity of the disease vary depending on the specific genetic mutation. X-linked Alport Syndrome affects both males and females, but males are more likely to develop severe symptoms than females.

Causes of Alport Syndrome

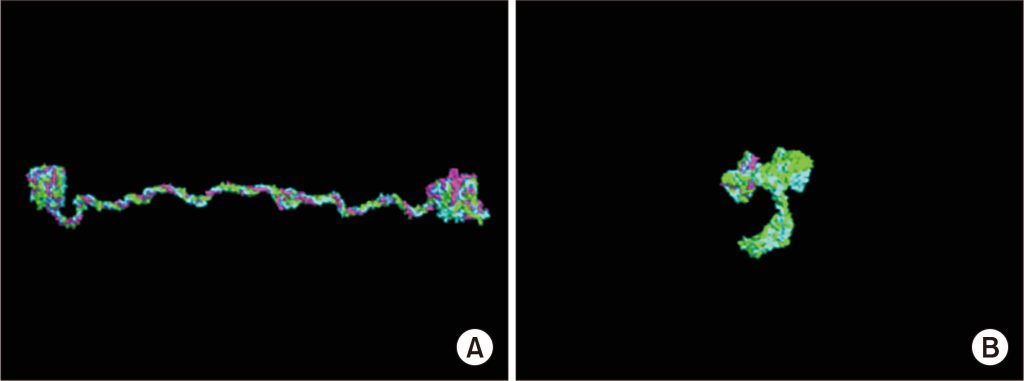

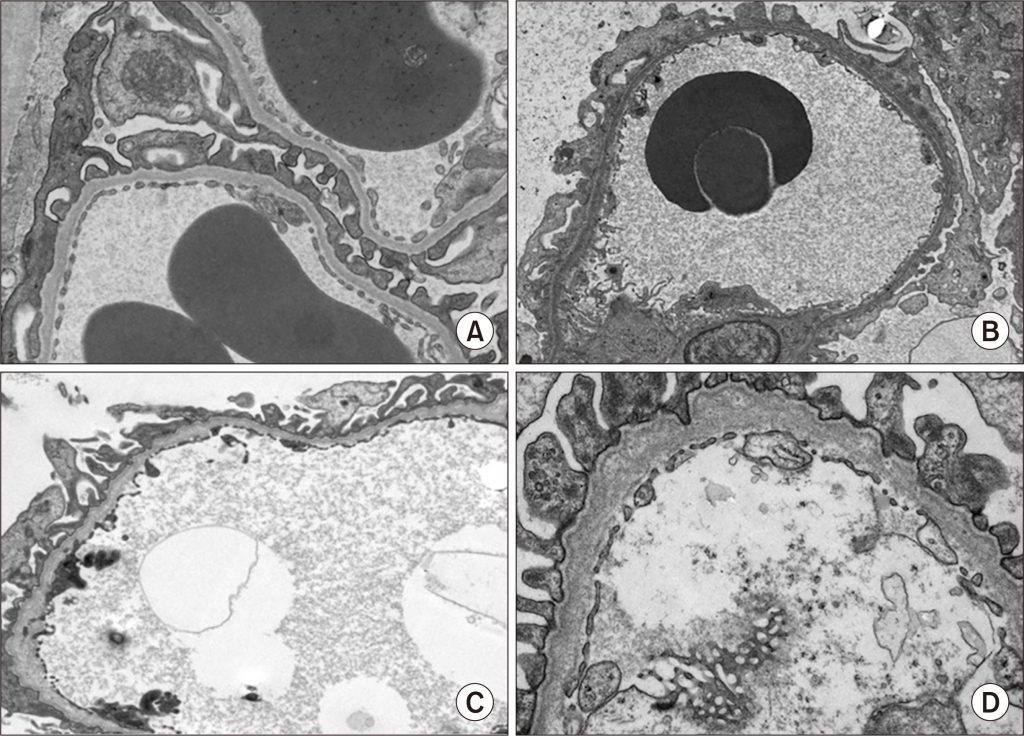

This disease is caused by mutations in the COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 genes, which encode the α3, α4, and α5 chains of type IV collagen. These chains form a triple-helical structure, which tightly binds with other triple helices to create the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). A pathogenic mutation in the COL4A5 gene or two pathogenic mutations in the COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes lead to highly ordered GBM degradation, accelerating glomerulosclerosis, which ultimately results in renal dysfunction.

Figure 1. (A) Normal type IV collagen triple-helix structure. (B) Missense mutation in COL4A5 disrupting the triple-helix structure. [1]

Figure 2. (A) Normal glomerular basement membrane (GBM). (B–D) GBM in Alport syndrome patients (mild to severe cases).

The COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes are located on chromosome 2q35–37, while COL4A5 is located on chromosome Xq22.

As a result, Alport syndrome follows three inheritance patterns:

- X-linked dominant inheritance (80%–85%)

- Autosomal recessive inheritance (15%)

- Autosomal dominant inheritance (5%)

Based on the different genetic inheritance patterns, Alport Syndrome can be categorized into several subtypes [2].

Genetic Inheritance and Clinical Features of Alport Syndrome

| Inheritance Pattern | Causative Gene | Hematuria | Proteinuria | Clinical Features | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XLAS Male (X-linked Alport Syndrome) | COL4A5 gene hemizygous mutation | Nearly 100% microscopic hematuria | Nearly all cases | 32%–83% hearing loss 6%–35% eye abnormalities | 50% progress to ESKD before age 25 90% progress to ESKD before age 40 |

| XLAS Female | COL4A5 gene heterozygous mutation | >90% microscopic hematuria | ~70% | 6%–28% hearing loss 2%–15% eye abnormalities | Most retain kidney function beyond age 30, 16% progress to ESKD before age 65 |

| ARAS (Autosomal Recessive Alport Syndrome) | COL4A3 or COL4A4 homozygous/compound heterozygous mutation | 100% microscopic hematuria | Nearly all cases | 60% hearing loss 60% eye abnormalities | 50% progress to ESKD before age 22.5 |

| ADAS (Autosomal Dominant Alport Syndrome) | COL4A3 or COL4A4 heterozygous mutation | ~90% microscopic hematuria | ~70% | <10% hearing loss <5% eye abnormalities | 50% progress to ESKD before age 67 |

| Digenic Alport Syndrome | COL4A3 and COL4A4 gene mutations | - | ~70% | ~30% hearing loss <5% eye abnormalities | 50% progress to ESKD before age 54 |

| COL4A5 + COL4A3 or COL4A4 Mutation | COL4A5 mutation combined with COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutation | Males: 100% microscopic hematuria Females: 100% microscopic hematuria | Males: ~90% Females: ~60% | Males: ~60% hearing loss Females: ~20% Males: ~50% eye abnormalities Females: ~10% | Males: 50% progress to ESKD before age 25 Females: 10% progress to ESKD before age 45 |

Notes:

- XLAS: X-linked Alport Syndrome

- ARAS: Autosomal Recessive Alport Syndrome

- ADAS: Autosomal Dominant Alport Syndrome

- ESKD: End-stage kidney disease

Current Drug Treatments for Alport Syndrome

At present, there is no cure or gene therapy for Alport Syndrome. Treatment strategies primarily focus on early pharmacological intervention to slow disease progression and delay the onset of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD); otherwise, kidney replacement therapy is required.

The 2023 Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Alport Syndrome states that renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors are currently the primary recommended drugs for slowing the progression of kidney disease in Alport Syndrome.

The following table summarizes the current drug development progress for Alport Syndrome, but no specific approved drugs are available for this indication yet.

Alport Syndrome Drug Development Progress

| Drug Name | Research Status | Originating Company |

|---|---|---|

| Sparsentan | Approved for market | Travere Therapeutics |

| Atrasentan | Pending market approval | Chinook Therapeutics |

| Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy | Clinical Phase II | Guangzhou Ruitai Animal Protection Hospital |

| Bardoxolone Methyl (Methylbardoxolone) | Clinical Phase III | Kyowa Kirin Co Ltd; Reata |

| Vonalexor | Clinical Phase II | Poxel Sa |

| R3R-01 | Clinical Phase I | River 3 Renal Corp |

| Exaluren | Clinical Phase II | Technion-Israel Institute of Technology |

| TJ-0113 | Clinical Phase II | Zhejiang Tianyu Sheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. |

| Setanaxib | Clinical Phase II | Genkyotex Sa |

* Note: None of the listed drugs have been approved specifically for Alport Syndrome treatment.

Alport Syndrome-Related Animal Models

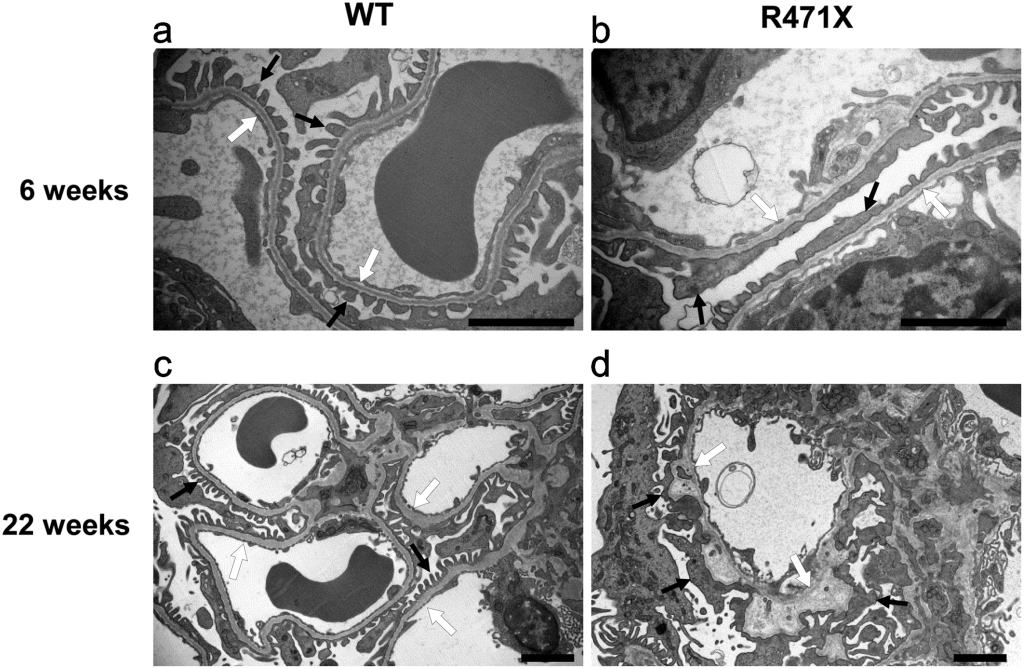

In 2019, a Japanese laboratory developed an X-linked Alport disease model by introducing a human-equivalent mutation (R471X) into mice using a homologous recombination method. This model resulted in COL4A5 nonsense mutations, preventing the normal expression of the protein.

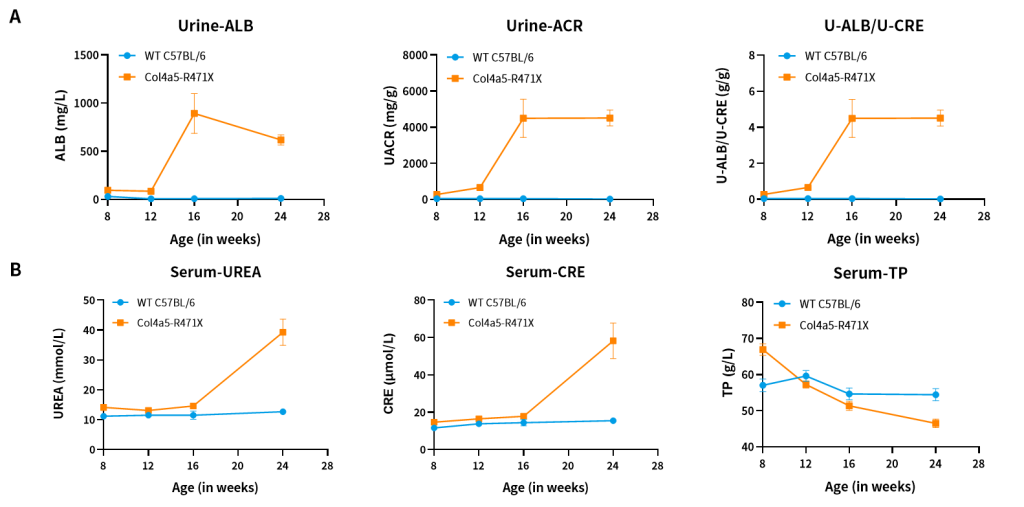

Urine analysis showed significantly elevated protein and creatinine levels in R471X mice compared to the control group. While total protein levels in blood remained unchanged, blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels showed a notable increase. Immunohistochemical analysis of six-week-old mice also revealed tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the kidneys of R471X mice.

Figure 3. Wild-type (WT) and mutant (R471X) male mouse glomerular basement membranes [3].

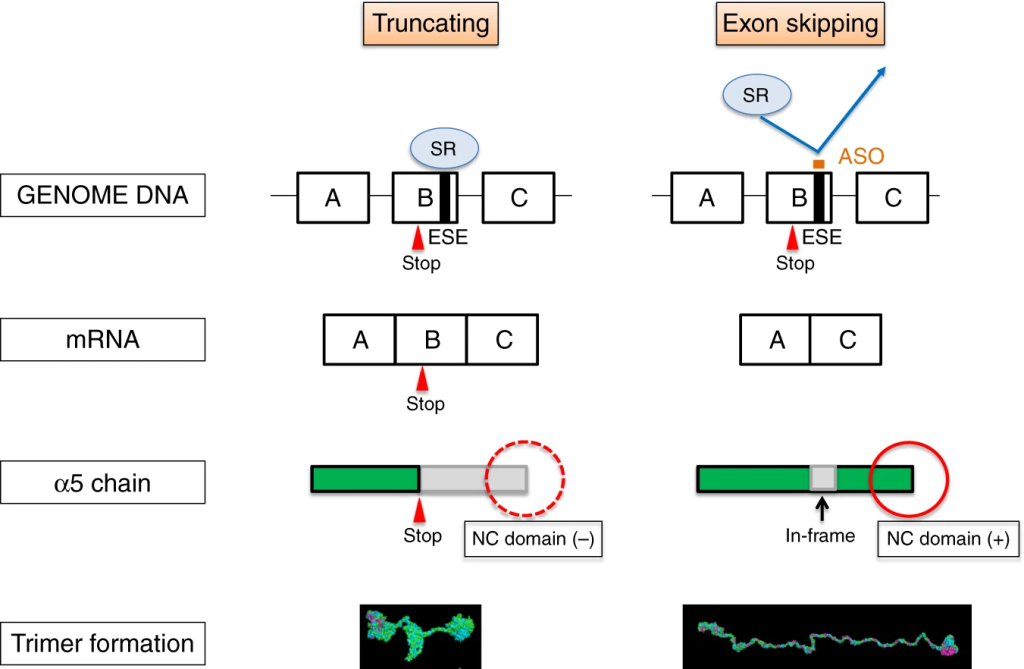

The following year, to further study Alport disease models, the same research team used antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy to induce exon skipping in the COL4A5 gene, leading to the formation of normal collagen IV triple helices and slowing the progression of kidney failure. The study demonstrated promising results in animal models, providing new insights for future drug development for Alport syndrome.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapy rescuing XLAS animals from developing ESRD. [4]

GenoBioTX Related Animal Models

Rare diseases are a global public health challenge. As a company specializing in model organisms, GenoBioTX has long been committed to research on gene therapies for rare diseases. We have developed an X-linked Alport disease model to support research on the mechanisms of Alport disease and provide a powerful tool for evaluating drug efficacy and safety.

The specific information is as follows:

| Gene | Mouse Strain | Mouse Type | Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Col4a5 | Col4a5-R471X | Point mutation mouse | NM-KI-200183 |

| Col4a5 | Col4a5-R373X | Point mutation mouse | NM-KI-200296 |

Col4A5-R471X Related Validation and Drug Efficacy Data:

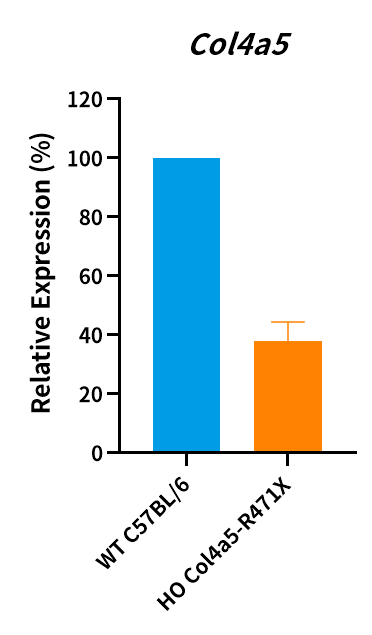

Figure 5. Col4a5 mRNA level was measured in Col4a5-R471X male mice and the point mutation of Col4a5 has been verified by sequencing (n=3, male, 7 weeks old). HO, homozygous; WT, wild type.

Figure 6. The results of urine (A) and blood (B) biochemical indicators in Col4a5-R471X mice (n=2 male and 6 female).

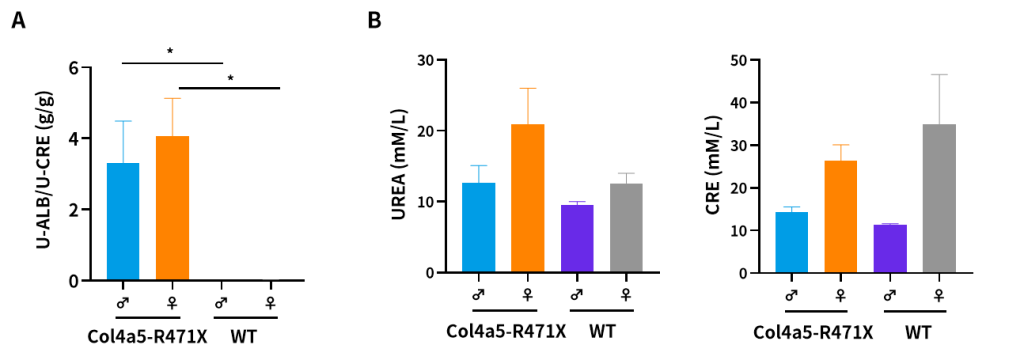

Figure 7. The results of urine (A) and plasma (B) biochemical indicators in 21-weeks-old Col4a5-R471X mice (n=3/group). (Data from a cooperator)

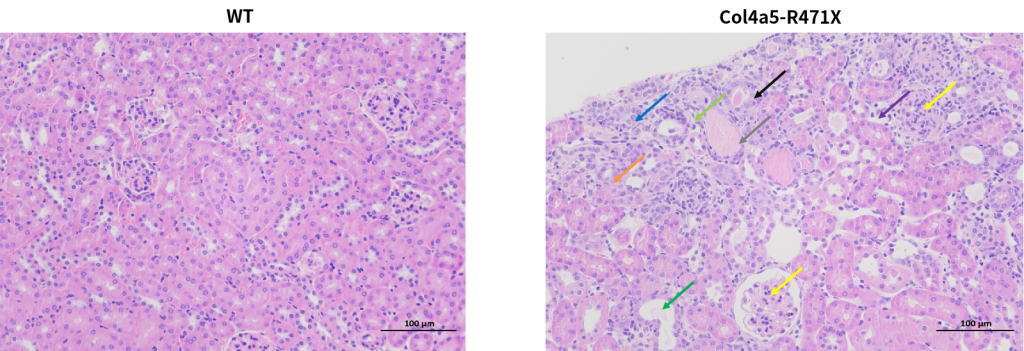

Figure 8. Marked glomerular changes are recognized in all (8/8) R471X mice of 23 weeks of age. The renal cortex shows uniform glomerular distribution, with mesangial matrix proliferation and mild sclerosis (yellow arrow). Renal tubular changes include epithelial edema (blue arrow), atrophy (orange arrow), dilation (green arrow), and necrosis (black arrow). Connective tissue proliferation (light green arrow), lymphocyte infiltration (purple arrow), and occasional protein casts (gray arrow) are noted. Such lesions are entirely absent in controls of the same age. Scale bar = 100 μm; magnification, 200×.

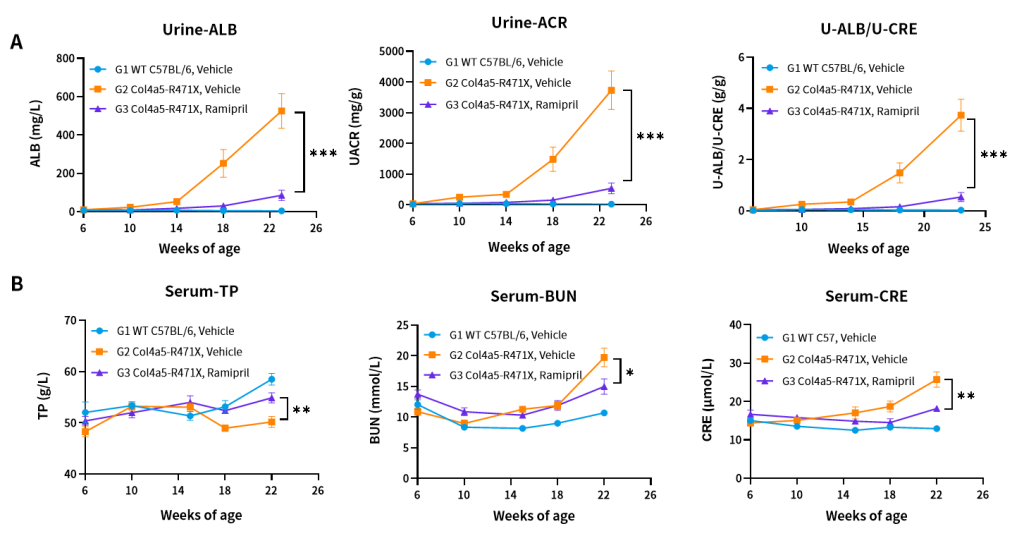

Figure 9. Effects of Ramipril (10 mg/kg) on urine (A) and blood (B) biochemical indicators of Col4a5-R471X mice over a 16–17 weeks treatment period (6 weeks of age at initiation time, n=4–5 male and 4–5 female in each group).

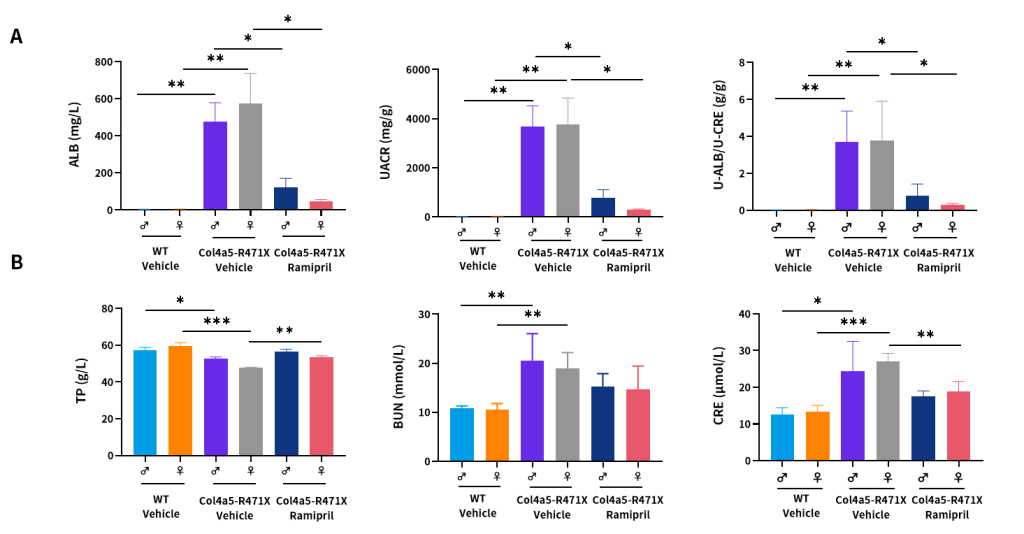

Figure 10. Effects of Ramipril (10 mg/kg) on urine (A) and plasma (B) biochemical indicators of male and female Col4a5-R471X mice over a 16–17 weeks treatment period respectively (6 weeks of age at initiation time, n=4–5 male and 4–5 female in each group).

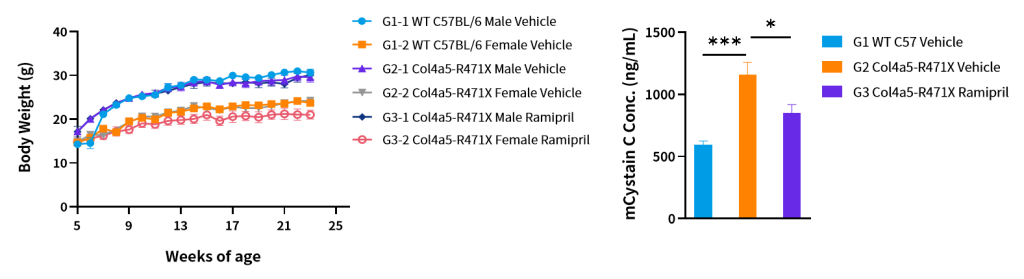

Figure 11. Body weight (A) and serum mCystatin C (B) of Col4a5-R471X mice over a 17 weeks treatment period (6 weeks of age at initiation time, n=4–5 male and 4–5 female in each group).

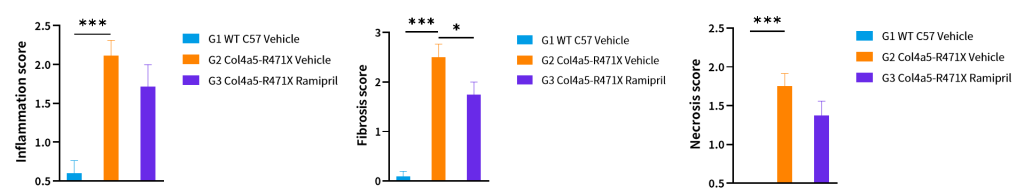

Figure 12. Histopathology changes of Col4a5-R471X mice over a 17 weeks treatment period (6 weeks of age at initiation time, n=4–5 male and 4–5 female in each group). Data are presented as mean and ± SEM.

Appendix: Pathological Evaluation Criteria [5]

Four-Level Grading System

| Grade | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Within normal range | Under research conditions, considering factors such as animal age, sex, and strain, the tissue is considered normal. Changes occurring under other conditions are considered abnormal. |

| 1 | Very mild | Changes are just beyond the normal range. |

| 2 | Mild | Observable pathological changes, but not severe. |

| 3 | Moderate | Significant pathological changes with a high likelihood of worsening. |

| 4 | Severe | Extremely severe pathological changes, where lesions occupy the entire tissue or organ. |

Reference

[1] Nozu K, Takaoka Y, Kai H, et al. Genetic background, recent advances in molecular biology, and development of novel therapy in Alport syndrome. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020;39(4):402–413. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.20.111

[2] https://www.cma.org.cn/?c=0

[3] Hashikami K, Asahina M, Nozu K, Iijima K, Nagata M, Takeyama M. Establishment of X-linked Alport syndrome model mice with a Col4a5 R471X mutation. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2018;17:81–86. Published 2018 Dec 12. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2018.12.003

[4] Yamamura, T., Horinouchi, T., Adachi, T. et al. Development of an exon skipping therapy for X-linked Alport syndrome with truncating variants in COL4A5. Nat Commun 11, 2777 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16605-x

[5] Peter. Mann 等. 大鼠和小鼠病理变化术语及诊断标准的国际规范(INHAND)[M]. 杨利峰, 周向梅, 赵德明主译. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2019.